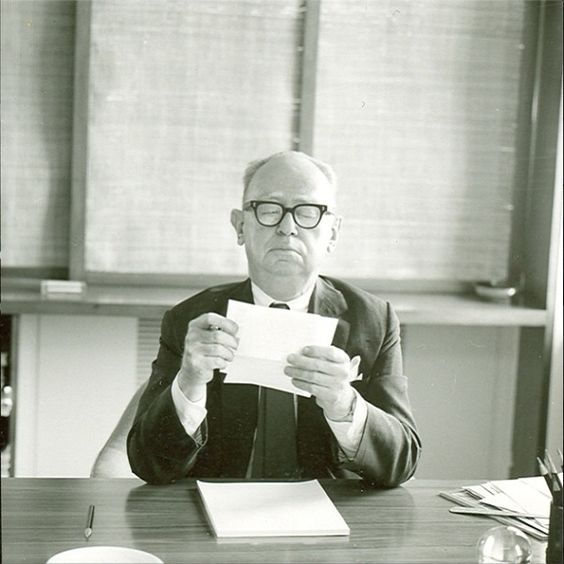

Leo Burnett, The Man Behind the Legend

He was christened Leo Noble Burnett in St. Johns, Michigan on October 21, 1891, the first of four children born to Rose and Noble Burnett. The name came to him by accident. An abbreviation of his intended name, George, was misread by hospital officials completing the birth certificate. So instead of Geo. Noble Burnett, the world was given Leo.

He was christened Leo Noble Burnett in St. Johns, Michigan on October 21, 1891, the first of four children born to Rose and Noble Burnett. The name came to him by accident. An abbreviation of his intended name, George, was misread by hospital officials completing the birth certificate. So instead of Geo. Noble Burnett, the world was given Leo.

The elder Burnett owned a dry-goods store, where Leo eventually gained his first advertising experience designing and lettering show cards.

The elder Burnett owned a dry-goods store, where Leo eventually gained his first advertising experience designing and lettering show cards.

During high school, Leo was a corresponding reporter for several county-seat weeklies. After graduation, he taught in a one-room schoolhouse in rural St. Johns, but the position was only temporary. Destiny had greater “teaching” responsibilities in store for Leo Burnett.

Leo entered the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in 1910 and graduated four years later with a degree in journalism. (He paid for his education working as a night editor of the Michigan Daily, and by lettering show cards for a department store.) His first job after college was as a reporter for the Peoria, (Illinois) Journal. He earned $18 a week.

Leo entered the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in 1910 and graduated four years later with a degree in journalism. (He paid for his education working as a night editor of the Michigan Daily, and by lettering show cards for a department store.) His first job after college was as a reporter for the Peoria, (Illinois) Journal. He earned $18 a week.

He stayed with the Journal for one year, but advice from a former classmate, Owen B. "Obie" Winters (who later became an advertising great), rang in his ear: "You’re a sucker to stay in Peoria...the automobile industry is the place to be."

When a former college professor wrote to Leo that the Cadillac Motor Car Company in Detroit was looking for someone to edit a house magazine, he jumped at the chance to apply. An essay on neatness won him the job. In time, Cadillac assigned its advertising responsibilities to Leo as well. Thus began what Bill Tyler, a one-time Burnett copywriter, said was the "most intense love affair with advertising in the history of the business."

When a former college professor wrote to Leo that the Cadillac Motor Car Company in Detroit was looking for someone to edit a house magazine, he jumped at the chance to apply. An essay on neatness won him the job. In time, Cadillac assigned its advertising responsibilities to Leo as well. Thus began what Bill Tyler, a one-time Burnett copywriter, said was the "most intense love affair with advertising in the history of the business."

Leo’s "other" love affair developed in 1917 when he met Naomi Geddes, who was working as a restaurant cashier near the Cadillac Company. She was reading William De Morgan’s A Likely Storyand, as he was paying his tab, young Leo suggested she read Joseph Vance. The next time she worked, Naomi found Leo’s used copy of the book at her counter.

They were married one year later in Detroit, shortly before Leo joined the United States Navy for six months during World War I. He spent his service building a breakwater in Lake Michigan, a fact he later told his children "caused a great deal of agitation among the German High Command and was probably responsible for the loss of Verdun."

They were married one year later in Detroit, shortly before Leo joined the United States Navy for six months during World War I. He spent his service building a breakwater in Lake Michigan, a fact he later told his children "caused a great deal of agitation among the German High Command and was probably responsible for the loss of Verdun."

Leo’s postwar stint with Cadillac ended when several employees broke away to form the brand new LaFayette Motors, the "American Rolls-Royce." Leo moved with them to Indianapolis as advertising manager, but when the suffering LaFayette Company retreated to Wisconsin, Leo signed on as creative head of the Homer McKee advertising agency in Indianapolis. There he wrote ads for 10 years. During that time, he and Naomi became the parents of two boys and a girl.

Shortly after the stock market crash in 1929, Homer McKee lost an important automobile account, and Leo decided to migrate with his family to a more stable environment. They moved to Chicago, where he went to work for Erwin Wasey as Creative Vice President. Wasey was enjoying temporary status as the largest advertising agency in the world. It was 1930.

Shortly before Leo joined Erwin Wasey, the company had moved its headquarters to New York. It soon became evident that the agency favored its eastern clients and the hard-sell New York approach to advertising. Several Midwestern clients were becoming disenchanted with Erwin Wasey.

Shortly before Leo joined Erwin Wasey, the company had moved its headquarters to New York. It soon became evident that the agency favored its eastern clients and the hard-sell New York approach to advertising. Several Midwestern clients were becoming disenchanted with Erwin Wasey.

By 1934, three such clients were pressuring Leo to open his own shop, but he was reluctant to walk away from Erwin Wasey. When Art Kudner another Wasey executive, broke away with Buick, Goodyear, and General Motors to form his own agency in early 1935, Leo was finally convinced to do the same.

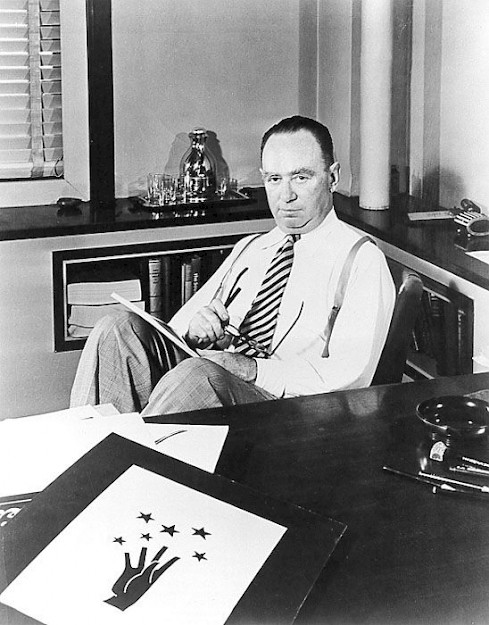

And with $50,000, he opened the doors that bore his name for the first time on August 5, 1935, eager to show the New York-based industry what his brand of advertising was all about. Leo was 44 years old.

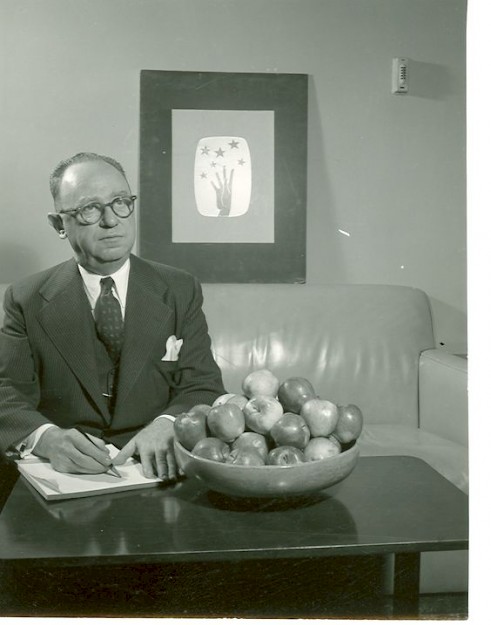

Leo wanted to create superior advertising. He believed that "lurking in every product which deserves success is a reason for being and a reason for buying which is deeply felt by the manufacturer and which, if captured and communicated, is the best of all possible advertising, because it is honest and believable. The trick is to make it interesting and exciting." Leo set out to make that kind of advertising.

Leo wanted to create superior advertising. He believed that "lurking in every product which deserves success is a reason for being and a reason for buying which is deeply felt by the manufacturer and which, if captured and communicated, is the best of all possible advertising, because it is honest and believable. The trick is to make it interesting and exciting." Leo set out to make that kind of advertising.

Leo wrote many ads for his new company, although his role eventually became editor rather than a writer.

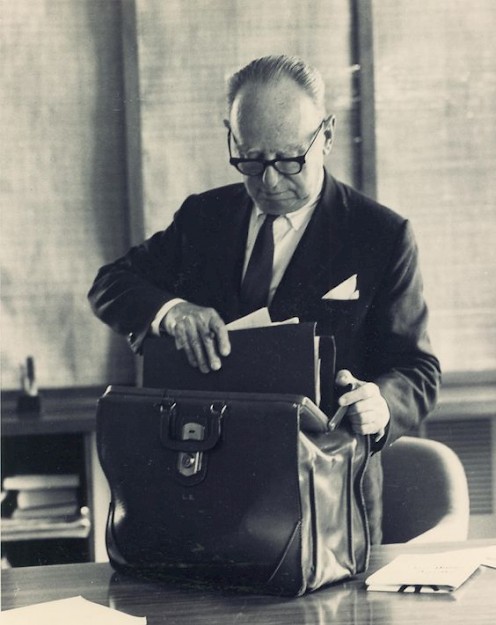

Between 8:00 and 8:30, Leo would rummage through art directors’ offices -- a famous habit that kept him abreast of the agency’s creative output.

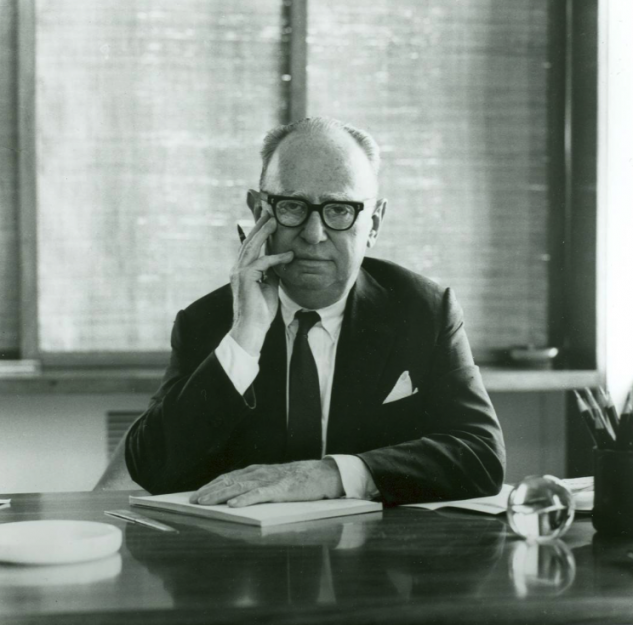

Leo’s capacity for endless labor was the envy of the industry, and it inspired the same dedication in those who worked for him. A time buyer once explained, "We work hard and long hours, but there’s a difference. Not long ago, I had to go into the office on Saturday. When I signed in, Mr. Burnett had signed in ahead of me. He was there when I left. He was signed in on Sunday when I went back... You don’t mind it so much when you know the boss is working that way, too."

Leo’s capacity for endless labor was the envy of the industry, and it inspired the same dedication in those who worked for him. A time buyer once explained, "We work hard and long hours, but there’s a difference. Not long ago, I had to go into the office on Saturday. When I signed in, Mr. Burnett had signed in ahead of me. He was there when I left. He was signed in on Sunday when I went back... You don’t mind it so much when you know the boss is working that way, too."

According to a former Burnett account executive, "He was not an ivory tower kind of guy. He was down there with his shirt sleeves rolled up and the black pencils scrubbing around."

Leo Burnett adored the advertising business. DeWitt O’Kieffe, one of the founders, once said of his boss, "Leo had more fun at the agency than a person taking the day off to play golf." An Eastern client once described Leo as "a mid-continent person -- frank and lots of fun. When the pressure is hardest and things look blackest, Leo will leap up in the middle of a meeting, look around, grin and comment, ‘Isn’t this fun?’"

In 1942, Leo purchased a farm near Lake Zurich, Ill., which inspired in him an intense love of nature. He planted more than 20,000 trees on the farm and could identify several hundred varieties of wild flowers.

After the shock of Pearl Harbor, Leo plunged into work for The War Advertising Council. One of his first acts was volunteering the agency’s time in the crusade to collect scrap metal for the war effort.

The response was so positive, the Council was asked to send a representative to a War Production Board meeting in Washington. Leo attended. He took with him a portfolio stuffed with layouts, copy and plans for a complete campaign.

Leo was honored for his contributions to wartime advertising in 1945. In 1947, he authored and compiled "Good Citizen," a book of America’s rights and privileges, published by the Heritage Foundation.

Later that year, Leo suffered a mild heart attack, forcing him to ease his schedule somewhat. So the famous "sessions at the farm" were initiated.

On Saturday mornings, or Friday nights, or Sundays, a cavalry of art directors, writers, account executives, research people, etc. would converge on Leo’s office at the farm — a tradition that continued for many years. Several enduring ideas, such as the Marlboro cowboy, were created during those sessions.

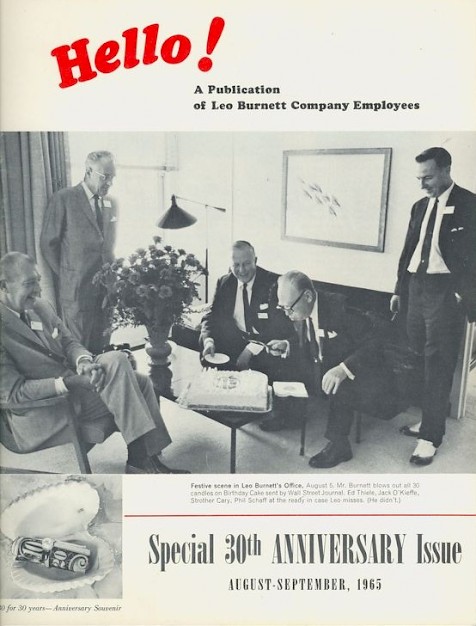

On its 25th anniversary, the Leo Burnett Company was the sixth-largest agency in the U.S., billed $110 million and had 900 employees and 24 clients on its roster.

Leo Burnett’s photograph -- along with other advertising giants -- graced the cover of Time on October 12, 1962, when the publication featured an article entitled "Madison Avenue." And in 1966, the Chicago Chapter of the American Marketing Association named him "Marketing Man of the Year." But Leo’s favorite citation was bestowed upon him in 1963 when the University of Missouri gave him its Honor Award for Distinguished Service in Journalism.

Leo’s greatest admirers were the people who worked with him -- the copywriters and art directors who, after a week of 12-hour days, would seethe during a creative review conference when Leo snapped, "No. Not good enough." But they somehow returned the following day with ads that were better. And the account executives who managed to remain calm when in the middle of a client presentation that was going fine, Leo interrupted with, "Wait! I think I have a better idea."

Leo Burnett was a client’s dream. He purchased 100 shares of stock in every new client. His pockets constantly bulged with Philip Morris cigarette packages. For years, every shoe he wore was made by the Brown Shoe Company, and until the day he died, Special K was his regular breakfast.

Leo did what he set out to do, and that was to create superior advertising for his clients. In doing so, he created a Chicago School of Advertising. In a 1965 speech to the Chicago Ad Club, Leo said, "Any canvases of New York agencies will show, of course, that a lot of their star performers were originally cow-milking yokels from the Midwest. I suppose we can be proud of that, but I think Chicago advertising has now reached a point where we can stop being a way-station for talent, and that making good in Chicago is in every way as rewarding as making the grade in New York."

As the ’60s matured, Leo found it increasingly difficult to maintain his pace with the agency. Illness kept him away from the office more and more, and he required rest periods on the days he was present. But his enthusiasm never waned.

As the ’60s matured, Leo found it increasingly difficult to maintain his pace with the agency. Illness kept him away from the office more and more, and he required rest periods on the days he was present. But his enthusiasm never waned.

In 1967, Leo retired from active management, announcing that he was "stepping down, but not out." Even so, his presence at the agency remained obvious. He traveled to the office at least twice a week and continued to generate enough paperwork to keep two secretaries busy full-time.

His last day at the office was June 7, 1971. He worked for several hours, traveled home to Lake Zurich, and ate dinner with Naomi. Later that evening, Leo suffered a heart attack on his Lake Zurich farm and died quietly in his sleep. He was 79 years old.

In his wake, Leo left one of the world’s largest and most respected advertising agencies, with nearly 9,000 intensely loyal employees, and an influence on the advertising industry which would never fade.